Saturday, June 10, 2006

Back to the Smut

Blogger permitting, let us now return to the subject of dirty art.

On Thursday I had a good idea where I was headed with this, but then the Technical Shit intervened, and now my categories are confused. Thus, indulge me:

What has GONE BEFORE, for the benefit of NEW READERS and the ABSENT-MINDED BLOG-OWNER:

Your host, Thers, was ruminating on Art and Censorship, in the context of 1920s blues lyrics, Joyce's Ulysses, and Flaubert. He noted that for all of these, censorship proved to be a significant obstacle -- and yet also seemed to fuel the artist's creativity. Blues singers, like these writers, faced fairly serious sanctions in the pursuit of their Art. Yet, these challenges in the end only seemed to spur them to greater artistic achievements.

This led me to inquire:

Can art be any good if it is in not in some way transgressive? Or was, once? And why? And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?My wonderful commenters -- beg pardon, my "minions," "bitches," and "cohort of charlatans" (pace recent fulminations elsewhere in blogland) -- quickly threw cold water on all this, pointing out two obvious things, namely that the dynamic I am referencing is relatively new in Western culture, dating from about the middle of the 19th century, and also that it is not necessarily The Nasty that causes folks to become angered at Art: it is its formal transgressions, its refusal to be interpreted in any terms other than its own.

Given all this, has not censorship in the long run been GOOD for art and artists?

If so, then on what basis do we oppose the censorship of artistic production?

OK, it was at this latter point that I started to get all fuzzy, using terms like "the censorship impulse" or whatever that my friends were kind enough not to point out were pretty much just hooey. So let me backtrack a bit.

I'm convinced by Bourdieu's argument, as laid out in The Field of Cultural Production and more fully and systematically in the Rules of Art, that by and large cultural production -- that is, anything anyone makes as a cultural product, music, paintings, cartoons, books, movies -- can be divided into two separate but related worlds: what he calls the field of general production and the field of restricted production.

Now, the first, elementary, and crucial point here is to do with the concept of the "field." What he means here is that the big giant world we live in is subdivided into separate smaller worlds, and humans define themselves according to where they stand or would like to stand in these worlds. So we all belong in one way or another to a "family field," and a "work field," or a "sports fan field," or a "political field," or whatever. Now, we never get to completely and only rarely partially define the rules of the various fields we exist in, because these fields existed before we did, and because they are always populated by people other than us. Some fields we are born into; some, we choose. Either way, our lives are like a series of games -- we find ourselves on different boards all the time, and have certain options for how we move, and can adopt certain strategies -- but we are always playing, and always to win, however we define it. (Please hold your questions until the end of the tour. Thanks.)

Now, as to art and culture. The difference between the two forms of cultural production, the general and the resticted, is at once simple and profound. Let's use movies as an example.

We all know that there are two kinds of movies, studio pictures and independents. All major studio movies are subjected to test screenings, focus groups, and so on. Studios thus spend a lot of time and money essentially making sure that people will like their movie before most people are able to see it. So what are they doing? They are, in short, trying to ensure that what they produce will conform to already generally accepted rules of what distinguishes a good movie from a bad one. This is what characterizes the field of general production: an attempt at conformity to accepted artistic rules in an attempt to achieve financial profit.

Now, independent movies. The producer of a non-studio movie is trying to do two things that are different from the big studios: she or he is trying to make the audience change their categories of perception. That is, she won't make the two young people fight and then fall in love; he won't make the good ninja beat all the bad ninjas. The story and its means of presentation will not be those that are most conventional. And, of course, this means that the producer has something else in mind beyond financial profit: that is, some sort of artistic profit. And what is artistic profit? Hard to say... but whatever it is, it is not money, that is for sure. Great artists, of course, are supposed to starve.

This is the field of restricted production. Why restricted? Because it is restricted to people who are themselves producers. This is a market distinction. If you want to succeed generally, you try to appeal to everyone. If you want to succeed artistically, your audience is primarily those people who intimately know the field you exist in: that is, other artists, established critics, patrons, the jerk in your film school whose stuff you hate but who has some sort of connections, hip magazinje writers, scenesters... people who are producing "insider" opinions, essentially.

Now, here we make a great leap forward. Why? Because we can see that what is at stake in any censorship controversy is not so much the actual nasty expression, but a much wider and essentially political struggle.

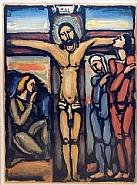

I'll get back to this, and explain the Rouault, tomorrow. Or Monday.

Comments:

<< Home

Interesting. At the end there, it sounds like there are two different quests at work in the general and restricted fields: The quest for Popularity, and the quest for Quality. Of course, it is possible for the major studio movie to be Quality, and it's possible for the indie film to become Popular (and it's *certainly* possible for it to be utter crap).

Considering how many major studio movies try (or pretend) to push the envelope of sexuality (or violence, or bathroom humor) to enhance their Popularity, it seems like cultural transgressions aren't really a distinguishing factor between the general and restricted fields, so when you talk about "formal transgressions", does that include stylistic ones, like The Hero *not* getting The Girl?

What about total crap that's transgressive for the sake of being transgressive, and doesn't actually have anything else going for it (I'm thinking Howard Stern and other shock jocks)? Or is it the subtlety of transgression that makes something great art? As you seem to suggest, is there perhaps not currently *enough* censorship to inspire artistic ways of getting around it?

(This is not my field and I just woke up, so this may all be completely puerile and/or incoherent...)

Considering how many major studio movies try (or pretend) to push the envelope of sexuality (or violence, or bathroom humor) to enhance their Popularity, it seems like cultural transgressions aren't really a distinguishing factor between the general and restricted fields, so when you talk about "formal transgressions", does that include stylistic ones, like The Hero *not* getting The Girl?

What about total crap that's transgressive for the sake of being transgressive, and doesn't actually have anything else going for it (I'm thinking Howard Stern and other shock jocks)? Or is it the subtlety of transgression that makes something great art? As you seem to suggest, is there perhaps not currently *enough* censorship to inspire artistic ways of getting around it?

(This is not my field and I just woke up, so this may all be completely puerile and/or incoherent...)

If you want to succeed artistically, your audience is primarily those people who intimately know the field you exist in: that is, other artists, established critics, patrons, the jerk in your film school whose stuff you hate but who has some sort of connections, hip magazinje writers, scenesters... people who are producing "insider" opinions, essentially.

I'm curious, though, how reception affects production, i.e., do people who think they're hip only accept certain styles of art and do artists, therefore, work to produce art that's "restricted"? Isn't there a certain amount off wink and nod and 'we get it but the public doesn't' that creates a well worn circular track of art for artists who only appreciate art for artists who...

I think that attitude is reflected by a lot of people - 'oh, those art house types think they're so cool, so I'll avoid their artsy art'. It's also reflected in the 'You used to be about the music, man!' phenomenon that's so prevalent in the music industry, and other art forms, I'd imagine. Green Day, for example, was abandonded and reviled by their original fan base and friends, hence the song 'Good Riddance'.

What's the tipping point where restricted artists become general artists? Is that point determined by the artists or the audience?

I'm curious, though, how reception affects production, i.e., do people who think they're hip only accept certain styles of art and do artists, therefore, work to produce art that's "restricted"? Isn't there a certain amount off wink and nod and 'we get it but the public doesn't' that creates a well worn circular track of art for artists who only appreciate art for artists who...

I think that attitude is reflected by a lot of people - 'oh, those art house types think they're so cool, so I'll avoid their artsy art'. It's also reflected in the 'You used to be about the music, man!' phenomenon that's so prevalent in the music industry, and other art forms, I'd imagine. Green Day, for example, was abandonded and reviled by their original fan base and friends, hence the song 'Good Riddance'.

What's the tipping point where restricted artists become general artists? Is that point determined by the artists or the audience?

Because we can see that what is at stake in any censorship controversy is not so much the actual nasty expression, but a much wider and essentially political struggle.

I think political and cultural norms -- for a given society -- are the boundaries that great artists break.

I've been ruminating on George Balanchine since you began this discussion. He was completely censored in his home country, so much so he had to leave. Yet in this country -- or the West more generally -- he was acclaimed, feted, and well compensated. What changed? Not the art, certainly. Rather the cultural and political norms of the society in which the art was made.

And yet, his art didn't actually transgress any norms of western society -- it changed some fundamental conventions of dance, but not in any transgressive way -- so why should it have been considered 'great art'? Because it had been transgressive at home? Or mebbe just because it was good?

I think political and cultural norms -- for a given society -- are the boundaries that great artists break.

I've been ruminating on George Balanchine since you began this discussion. He was completely censored in his home country, so much so he had to leave. Yet in this country -- or the West more generally -- he was acclaimed, feted, and well compensated. What changed? Not the art, certainly. Rather the cultural and political norms of the society in which the art was made.

And yet, his art didn't actually transgress any norms of western society -- it changed some fundamental conventions of dance, but not in any transgressive way -- so why should it have been considered 'great art'? Because it had been transgressive at home? Or mebbe just because it was good?

but a much wider and essentially political struggle.

which is what we see in any human endeavor.

you know in my earlier post, which blogger rejected, i had mentioned that when i studied mapplethorpe in school all the art critics derided him as a pornographer. when the curator was arrested in cincinatti in the rightwings constant attempt to derail the NEA, (my god how can we go on funding cultural accomplishment?) the critics rather abruptly changed their tune.

i think much of his work was pornographic. and underlying that is a pervading gestalt of religious iconography, also prevalent in much of western art.

you know it occurs to me that camus has a chapter on this in 'The Rebel', which i know is not considered to be one of his finer treatises, but i think probably addresses this issue in a relevant way.

i just like grating the satanic up against the holy, i think it's sexy.

which is what we see in any human endeavor.

you know in my earlier post, which blogger rejected, i had mentioned that when i studied mapplethorpe in school all the art critics derided him as a pornographer. when the curator was arrested in cincinatti in the rightwings constant attempt to derail the NEA, (my god how can we go on funding cultural accomplishment?) the critics rather abruptly changed their tune.

i think much of his work was pornographic. and underlying that is a pervading gestalt of religious iconography, also prevalent in much of western art.

you know it occurs to me that camus has a chapter on this in 'The Rebel', which i know is not considered to be one of his finer treatises, but i think probably addresses this issue in a relevant way.

i just like grating the satanic up against the holy, i think it's sexy.

Eli -- you're right about the two "quests." Another way of saying this is that for the studio, what matters is popularity and money: these are the two criteria for "success." For the "artist," what matters is specifically artistic success. This can indeed mean complete finacial ruin and unpopularity. Sometimes, such disasters can be taken as absolute proof of "artistic success"...

it was at this latter point that I started to get all fuzzy, using terms like "the censorship impulse" or whatever that my friends were kind enough not to point out were pretty much just hooey.

I thought I had!

And, of course, this means that the producer has something else in mind beyond financial profit: that is, some sort of artistic profit. And what is artistic profit? Hard to say... but whatever it is, it is not money, that is for sure.

Not exclusively money, at any rate. Of course, I've peeked at the end here, as far as Bourdieu is concerned, but this is indeed the main issue for me: what constitutes a "reward" for being an artist, and how much of that reward comes from things that are peripheral or irrelevant to the work itself?

A big issue, obviously, is "credibility," which can both validate the work, and serve as a reward for it. But a huge part of getting credibility is putting on an act, in such a way that one's preferred image will be reinforced and disseminated by magazines and so forth ("though he's the toast of five continents, Thers remains a humble man who is happiest among his flowers").

Two favorite options here are to pretend that the artist, the work, and the public image all fit together seamlessly - which they clearly don't in most cases - or to try and increase one's credibility among intellectuals by questioning how artists are represented. It starts to dawn on you that who you are and what you do has become almost totally reactionary; your work might be constrained by what sells, or by some romantic narrative about artistic integrity, or by your desire to define yourself in opposition to one or the other (or something else). Either way, the idea of autonomous private art in Adorno's sense, and "de-auraticized" mass art in Benjamin's, both begin to seem equally illusory. After a while, everything seems to boil down to power relations...they influence what you produce, and how it's received. It's a very disturbing realization, IMO.

I thought I had!

And, of course, this means that the producer has something else in mind beyond financial profit: that is, some sort of artistic profit. And what is artistic profit? Hard to say... but whatever it is, it is not money, that is for sure.

Not exclusively money, at any rate. Of course, I've peeked at the end here, as far as Bourdieu is concerned, but this is indeed the main issue for me: what constitutes a "reward" for being an artist, and how much of that reward comes from things that are peripheral or irrelevant to the work itself?

A big issue, obviously, is "credibility," which can both validate the work, and serve as a reward for it. But a huge part of getting credibility is putting on an act, in such a way that one's preferred image will be reinforced and disseminated by magazines and so forth ("though he's the toast of five continents, Thers remains a humble man who is happiest among his flowers").

Two favorite options here are to pretend that the artist, the work, and the public image all fit together seamlessly - which they clearly don't in most cases - or to try and increase one's credibility among intellectuals by questioning how artists are represented. It starts to dawn on you that who you are and what you do has become almost totally reactionary; your work might be constrained by what sells, or by some romantic narrative about artistic integrity, or by your desire to define yourself in opposition to one or the other (or something else). Either way, the idea of autonomous private art in Adorno's sense, and "de-auraticized" mass art in Benjamin's, both begin to seem equally illusory. After a while, everything seems to boil down to power relations...they influence what you produce, and how it's received. It's a very disturbing realization, IMO.

Sometimes, such disasters can be taken as absolute proof of "artistic success"

¿Can joo provide an example?

Curiosity y the gato, and all...

so.

¿Can joo provide an example?

Curiosity y the gato, and all...

so.

"Too many notes, my dear Mozart."

"No, your Grace. Just as many as are necessary."

Something like that. Blame "Amadeus" for my knowledge/ignorance.

Not exclusively money, at any rate. Of course, I've peeked at the end here, as far as Bourdieu is concerned, but this is indeed the main issue for me: what constitutes a "reward" for being an artist, and how much of that reward comes from things that are peripheral or irrelevant to the work itself?

No, but most artists eat. Shakespeare owned a piece of his theater company, was only too happy to be the King's playwright (or theater company, at least), and produced two plays a year (and they were good!) to make ends meet. Mozart struggled to get his work published or otherwise supported. Bach wrote his "Goldberg Variations" for a cup of gold ducats (or some kind of gold coin). Picasso was well aware of the market value of his work. And on and on and on....

Not arguing with Bourdieu (not yet, anyway), but it seems to me the market distinction Thers outlines is still a very limited one. What, then, do we make of cultures that don't distinguish between art and culture? (Doesn't this whole discussion depend on that distinction?)

Inquiring minds want to interfere.....

"No, your Grace. Just as many as are necessary."

Something like that. Blame "Amadeus" for my knowledge/ignorance.

Not exclusively money, at any rate. Of course, I've peeked at the end here, as far as Bourdieu is concerned, but this is indeed the main issue for me: what constitutes a "reward" for being an artist, and how much of that reward comes from things that are peripheral or irrelevant to the work itself?

No, but most artists eat. Shakespeare owned a piece of his theater company, was only too happy to be the King's playwright (or theater company, at least), and produced two plays a year (and they were good!) to make ends meet. Mozart struggled to get his work published or otherwise supported. Bach wrote his "Goldberg Variations" for a cup of gold ducats (or some kind of gold coin). Picasso was well aware of the market value of his work. And on and on and on....

Not arguing with Bourdieu (not yet, anyway), but it seems to me the market distinction Thers outlines is still a very limited one. What, then, do we make of cultures that don't distinguish between art and culture? (Doesn't this whole discussion depend on that distinction?)

Inquiring minds want to interfere.....

BTW, and completely OT, I think I've found out why "intent" is such a burning issue these days.

Eric Boehlert explains it all for you.

I know, I know, ugly topic. But when I saw this, I thought of Thersites.

Eric Boehlert explains it all for you.

I know, I know, ugly topic. But when I saw this, I thought of Thersites.

dammit, i google for smut and get this nonsense?

Isn't there a certain amount off wink and nod and 'we get it but the public doesn't' that creates a well worn circular track of art for artists who only appreciate art for artists who...

in some media, this is the only route to success, commercial or otherwise. do you see anyone painting or sculpting today that is even trying to reach a mass audience?

by the way, independent movies cost a hell of a lot of money, too. and often the backers can be a bigger headache than the studios because they've never been around a movie before and don't know their ideas are crap and dammit i'm a producer so why *shouldn't* the sisters take a shower together? the independent film maker, however, has the option of re-jiggering the script so that it will cost less to shoot. but i can tell you from experience that process sucks.

Isn't there a certain amount off wink and nod and 'we get it but the public doesn't' that creates a well worn circular track of art for artists who only appreciate art for artists who...

in some media, this is the only route to success, commercial or otherwise. do you see anyone painting or sculpting today that is even trying to reach a mass audience?

by the way, independent movies cost a hell of a lot of money, too. and often the backers can be a bigger headache than the studios because they've never been around a movie before and don't know their ideas are crap and dammit i'm a producer so why *shouldn't* the sisters take a shower together? the independent film maker, however, has the option of re-jiggering the script so that it will cost less to shoot. but i can tell you from experience that process sucks.

I just want to know if blogger et my very erudite post on how all this relates to dance?

Or is Thers just debating whether its worth posting or not?

Or is Thers just debating whether its worth posting or not?

RMJ -- well, the dynamic we're talking about is historically specific to Western culture since about the middle of the 19th century. I don't see the historical specificity of the argument as a weakness, but a strength -- it is very easy to make generalizations about Art and its universality, and there's nothing wrong with doing that. But then again, Art is produced by real people in real places, and the various ways they explain what they do are fascinating (especially when they are so blatantly contradictory, as they often are).

Hey, thanks for blogrolling me. Though it is the least you could do for one of your bitch minion cohorts . . .

Dunno, Thers--"art" has gotten more contradictory as Romanticism has claimed a greater and greater share of the cultural pie (an expression of self? An expression of the life force of the Universe? Must it be an expression at all?).

Which is ironic, in a conversation about Joyce, no?

On one side, you have Ambrose Bierce, whose "Devil's Dictionary" says "This word has no definition." The word, of course, is "art."

On the other, you have the field of Aesthetics, beyond which I've never read anything but Croce's "Aesthetics." And yeah, the discussion is clearly cultural specific, but doea art have to be about markets? Even as I ask that, I think: but if it isn't, what is it about?

How else, really, do we gauge the value of anything, in modern culture?

Which is ironic, in a conversation about Joyce, no?

On one side, you have Ambrose Bierce, whose "Devil's Dictionary" says "This word has no definition." The word, of course, is "art."

On the other, you have the field of Aesthetics, beyond which I've never read anything but Croce's "Aesthetics." And yeah, the discussion is clearly cultural specific, but doea art have to be about markets? Even as I ask that, I think: but if it isn't, what is it about?

How else, really, do we gauge the value of anything, in modern culture?

Capitalist values are one thing, and artistic values are another.

THEY ARE NOT THE SAME.

Aesthetics and money are quite different.

Well, they're not the same, but maybe they're not "quite different," either. If I'm ga-ga over Webern, and you're nuts for Clay Aiken, then - at least in some circles - I'm probably going to have more cultural capital than you. And if I can express my aesthetic preferences in the language appropriate to such circles, I'm probably going to enjoy social advantages that you won't if you can't speak that language.

So one similarity of aesthetics and money, at least, is that they can both produce social stratification.

Post a Comment

THEY ARE NOT THE SAME.

Aesthetics and money are quite different.

Well, they're not the same, but maybe they're not "quite different," either. If I'm ga-ga over Webern, and you're nuts for Clay Aiken, then - at least in some circles - I'm probably going to have more cultural capital than you. And if I can express my aesthetic preferences in the language appropriate to such circles, I'm probably going to enjoy social advantages that you won't if you can't speak that language.

So one similarity of aesthetics and money, at least, is that they can both produce social stratification.

<< Home