Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Smut

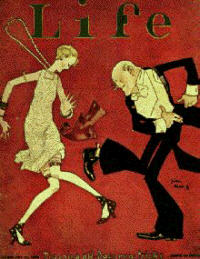

Phila will perhaps forgive me, as I can't remember exactly where he said this. But he was talking somewhere recently about how jazz singers in the 1920s would use euphemisms to get around censorship. "Sugar in my bowl" would stand in for a reference to sex, for instance.

The whole question of the complex interrelationship between censorship and art fascinates me. There is an interesting paradox: censorship of course endangers art. But at the same time, without censorship, would art really be? As Phila's observation suggests, censorship can have oddly productive effects. The slang and euphemisms in 1920s jazz, for example. The deliberate, sly sexuality inevitably inflects the music, the verbal marker of what makes it, well, different and therefore transgressive and so, well, appealing. And lasting.

You can't really separate out what jazz is and how it came to be what it is without remembering its disreputable roots. It's long since become a "legitimate" form, with univerity departments devoted to it, books written on it, events where people put on evening dress to see it performed, and so on. But the "heroic era" of its beginnings (term appropriated from Bourdieu) are an inextricable part of what it is -- and of its appeal. Just as in literature: Flaubert's trial is an itegral part of Flaubert's reputation. Or the Woolsey decision effectively legalizing Ulysses in the US is (for a while quite literally) an integral part of Ulysses itelf, as we receive it. Nobody picks up Ulysses randomly and just gets into it. Well, a few people do, maybe. But when they find out it's dirty -- well, that's what gets them past Chapter Three. "Ineluctable modality of the visible," oy. Where's the beating off and the S&M? And the poop jokes. Don't forget the poop jokes.

So let me open this up.

Can art be any good if it is in not in some way transgressive? Or was, once? And why? And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?

Given all this, has not censorship in the long run been GOOD for art and artists?

If so, then on what basis do we oppose the censorship of artistic production?

I'll be back with more on this later. Answer the questions correctly or be killed by circus freaks.

MORE

Hope you all don't mind me addressing the the excellent points raised in comments up here. I just want to sort out some of my thoughts, because the topic is being teased out in some interesting ways.

First -- we can make a distinction between "ancient" and "modern" art. As Flory, Speechless, and anonymous (please name yourself, BTW; it makes things easier) point out, referencing Michaelangelo, Phidias, and Bach, the relationship between censorship and art that I talked about, citing 1920s jazz, Flaubert, and Joyce, seems to be a relatively modern phenomenon.

So is it fair to say that something fundamental about the way we think about art and artists at some point changed? One thing that strikes me about the examples we've discussed is that the older ones are all religious, involving the patronage of the church. Since I asked a question about the Nasty, I suppose it is not surprising that these were the examples referenced. Shakespeare would be a more challenging example, given his sly earthiness. However, while we'd surely all agree that his plays are "art," it's not entirely clear that he did, or at least he saw them in a way that was not ours (otherwise he would have taken a lot more care of the texts). And it is also not clear just how "transgressive" these plays were in his time. To be sure, he talked about sex constantly. However, they were also a form of popular entertainment. What he saw as his more lasting stuff was the poetry, and when he published this, he made to secure an aristocratic patron. In that sense, what Shakespeare and Bach had in common was a sense that for art to be Art it needed a patron.

Obviously, patronage is not a part of artistic production nowadays -- not at least in the older sense of the word.

So, speaking broadly and allowing for many exceptions that prove the rule, whether we're speaking of religious or secular art, can we say that to really hone in on the phenomenon I began with (the relationship between art and censorship), we have to keep in mind how the economics of art have changed? Because this gets to something else. Art with a religious or noble patron is sanctioned by some outside agency. For Flaubert and Joyce, and for jazz singers, art was sanctioned by Art itself.

Is that a fair conclusion?

Second: the matter of form. As Shrimplate says:

But art is constantly seeking to transgress boundries of technique: perspective, abstraction, 12-tone-rows, free jazz, cow poop Virgin Marys, and the like.This is of course true. Even sticking with my examples, Flaubert, Joyce, and 1920s jazz, that would be true. In each case, the writer or musician's real "transgression" is formal. That is what really arouses anger about "new" or "high" art, by the way, or is at least integral to this anger. When people are outraged at art today it is not only because it breaks sexual (Mapplethorpe) or religious ("Piss Christ") taboos, but because it does so in the name of Art. It can't be dismissed as mere pornography or as just an offensive juvenile prank.

So if it is not merely sexual or even religious transgression in the modern period that makes art suceptible to "outrage," what is it about the formal transgressions that provokes what we might call the "censorship impulse"?

If you see what I mean...

Comments:

<< Home

Can art be any good if it is in not in some way transgressive?

The Mona Lisa. Botticelli's Venus. The Sistine Chapel.

I don't think any of them were considered transgressive even in their day.

Impressionism wasn't considered "good art" in its early days, but I'm not sure the connotation of transgressive would be appropriate.

The waltz as a dance was considered racy in Regency England, but the music wasn't.

The Mona Lisa. Botticelli's Venus. The Sistine Chapel.

I don't think any of them were considered transgressive even in their day.

Impressionism wasn't considered "good art" in its early days, but I'm not sure the connotation of transgressive would be appropriate.

The waltz as a dance was considered racy in Regency England, but the music wasn't.

Can art be any good if it is in not in some way transgressive?

Si.

Eet depends on the motive for creating thees piece een the first place. Self expression does no presuppose transgression, eh?

And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?

Si, eet simply depends on wheech line joo weesh to cross.

Een the heestory of art, (modern art een particular) there are many many examples of transgressions wheech were aesthetic een nature, rather than moral-specific.

Given all this, has not censorship in the long run been GOOD for art and artists? If so, then on what basis do we oppose the censorship of artistic production?

¿So joo propose that we all be happy weeth limiting our cultural intake to expression on the level of, say, Lawrence Welk re-runs?

so.

Si.

Eet depends on the motive for creating thees piece een the first place. Self expression does no presuppose transgression, eh?

And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?

Si, eet simply depends on wheech line joo weesh to cross.

Een the heestory of art, (modern art een particular) there are many many examples of transgressions wheech were aesthetic een nature, rather than moral-specific.

Given all this, has not censorship in the long run been GOOD for art and artists? If so, then on what basis do we oppose the censorship of artistic production?

¿So joo propose that we all be happy weeth limiting our cultural intake to expression on the level of, say, Lawrence Welk re-runs?

so.

Is Bach's 'B Minor Mass' art? Yes.

Is it in anyway transgressive? Not that I can see.

Does it reference the Nasty? Only insomuch as it references life and death, and human life isn't possible without the Nasty, therefore anything that references life by extension references the Nasty, so yes, it does reference the Nasty. However, in this case I think we can clearly see that referencing the Nasty, rather than being transgressive, is supportive of the status quo.

Is it in anyway transgressive? Not that I can see.

Does it reference the Nasty? Only insomuch as it references life and death, and human life isn't possible without the Nasty, therefore anything that references life by extension references the Nasty, so yes, it does reference the Nasty. However, in this case I think we can clearly see that referencing the Nasty, rather than being transgressive, is supportive of the status quo.

If one is to set up a kind of yin-yang relationship between art and censorship then I think that "transgression" would mostly apply to technique, not necessarily content, for over the centuries content has been relatively a stable element in art.

"Speechless" provides an example of this stability of content by noting that the life-death nexus, itself a yin-yang function, has long been one of the ongoing motifs in art.

But art is constantly seeking to transgress boundries of technique: perspective, abstraction, 12-tone-rows, free jazz, cow poop Virgin Marys, and the like.

"Speechless" provides an example of this stability of content by noting that the life-death nexus, itself a yin-yang function, has long been one of the ongoing motifs in art.

But art is constantly seeking to transgress boundries of technique: perspective, abstraction, 12-tone-rows, free jazz, cow poop Virgin Marys, and the like.

Can art be any good if it is in not in some way transgressive? Or was, once?

Of course. IIRC, some of Bach's work was done to glorify royalty, just for one example. And as Flory says, religious iconographic work is another example.

I think the notion that art has to be "transgressive" to be good is pretty much a 20th-c invention...or at least, that's where it became a truism. But it's fool's gold, by and large. Or often, anyway. (I tend to think it comes at least partially from increased self-consciousness about class, and the scorn heaped - often by themselves - on the bourgeoisie.)

And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?

Sure. What's "trangressive" depends on the cultural backdrop. In Nazi Germany, plenty of stuff was deemed transgressive without having any reference to sex.

The African American women blues singers interest me because they are not only censored by the general mores of the time, but also reacting against the "politics of respectibility" from middle-class black society.

As I said when I originally brought this up, what's even more interesting is the latitude these singers were granted. Performers on "race records" were able to get away with far more blatant obscenity than most white performers could.

About which, more later. I'm running out the door.

Of course. IIRC, some of Bach's work was done to glorify royalty, just for one example. And as Flory says, religious iconographic work is another example.

I think the notion that art has to be "transgressive" to be good is pretty much a 20th-c invention...or at least, that's where it became a truism. But it's fool's gold, by and large. Or often, anyway. (I tend to think it comes at least partially from increased self-consciousness about class, and the scorn heaped - often by themselves - on the bourgeoisie.)

And can art genuinely be "transgressive" without referencing the Nasty?

Sure. What's "trangressive" depends on the cultural backdrop. In Nazi Germany, plenty of stuff was deemed transgressive without having any reference to sex.

The African American women blues singers interest me because they are not only censored by the general mores of the time, but also reacting against the "politics of respectibility" from middle-class black society.

As I said when I originally brought this up, what's even more interesting is the latitude these singers were granted. Performers on "race records" were able to get away with far more blatant obscenity than most white performers could.

About which, more later. I'm running out the door.

What's "trangressive" depends on the cultural backdrop.

Indeed. And I think art can be "transgressive" if it simply addresses a subject in a way not typical of said culture, if it "transgresses" a worldview at all, even if not in a hostile way.

Indeed. And I think art can be "transgressive" if it simply addresses a subject in a way not typical of said culture, if it "transgresses" a worldview at all, even if not in a hostile way.

So if it is not merely sexual or even religious transgression in the modern period that makes art suceptible to "outrage," what is it about the formal transgressions that provokes what we might call the "censorship impulse"?

You're talking about now, or in the 20s? Because at this point, I'd say that the idea of transgression has become part of Marketing 101. (And even in the 20s, Cocteau was able to "shock" surrealists by going in for classicism.)

I guess I'd have to understand how much we can conflate the "censorship impulse," and formal censorship before I could take a stab at answering. But my gut feeling would be that defending turf is a big part of it. If you've devoted your life to studying baroque harmony, you may well take a dim view of 12-tone composition...not just because as a human being, you're prone to non-acceptance of the unfamiliar (cf. Nicholas Slonimsky in Lexicon of Musical Invective), but also because you feel the need to reassert your expertise and your relevance in a changing culture.

You're talking about now, or in the 20s? Because at this point, I'd say that the idea of transgression has become part of Marketing 101. (And even in the 20s, Cocteau was able to "shock" surrealists by going in for classicism.)

I guess I'd have to understand how much we can conflate the "censorship impulse," and formal censorship before I could take a stab at answering. But my gut feeling would be that defending turf is a big part of it. If you've devoted your life to studying baroque harmony, you may well take a dim view of 12-tone composition...not just because as a human being, you're prone to non-acceptance of the unfamiliar (cf. Nicholas Slonimsky in Lexicon of Musical Invective), but also because you feel the need to reassert your expertise and your relevance in a changing culture.

man, i left a big long post. which apparently did not make the blogger cut.

so let's boil it down.

Matisse or Picasso?

great post, got me think'n. art, like everything, has become exceptionally politicized.

so let's boil it down.

Matisse or Picasso?

great post, got me think'n. art, like everything, has become exceptionally politicized.

Sure. What's "trangressive" depends on the cultural backdrop. In Nazi Germany, plenty of stuff was deemed transgressive without having any reference to sex.

Let's go beyond Western culture. Will the "art" of Soviet Russia (ok...kind of western) or Maoist China be the decidedly non-transgressive state sanctioned art or the illegal and highly transgressive subversive works?

The Banmiyan(sp?) Buddhas were art by anyone's definition except the Taliban. But they were also decidedly not transgressive to anyone but the Taliban. How do they fit in?

I think in order to answer the question you have to know who gets to decide what transgressive means. And I don't think it's necessarily a religious issue. Norms and standards once enforced by religious authority are now enforced by civil authority....except for the Taliban......

Let's go beyond Western culture. Will the "art" of Soviet Russia (ok...kind of western) or Maoist China be the decidedly non-transgressive state sanctioned art or the illegal and highly transgressive subversive works?

The Banmiyan(sp?) Buddhas were art by anyone's definition except the Taliban. But they were also decidedly not transgressive to anyone but the Taliban. How do they fit in?

I think in order to answer the question you have to know who gets to decide what transgressive means. And I don't think it's necessarily a religious issue. Norms and standards once enforced by religious authority are now enforced by civil authority....except for the Taliban......

I think it's wrong and pointless to judge Art, as a whole.

Art's a nice guy and he's been under a lot of pressure, lately. Cut him some slack, man!

Art's a nice guy and he's been under a lot of pressure, lately. Cut him some slack, man!

I think that when people are oppressed their art explodes in a condensed and vivid form that can really get you. I'm thinking of the Amish women here and the art of their quilts. It's art and some of the quilts are mindboggling in their intensity. I read something similar in much of the Russian subversive art during the Soviet Union era.

So I don't think that censure is needed to get art but censure can't stop art from existing and it will exist in a different form because of the censuring.

The economics of art are interesting, but in some ways they give similar limits or constraints to art and make it appear in unusual ways. Think about the Nightwatch and how Rembrandt chose to make the people all different sizes even though they all paid the same amount to get included. I wouldn't have wanted to be in the meeting afterwards...

Having sexuality in art is not necessary, but it's one of the few things that tends to be censured to even the most powerful ones in society, so in that sense it always interests. For the rest of the people many other things are censured and banned and in that sense serve the role of "the nasty" to the privileged few. Just my opinion, of course, and I have no training in these fields, being a goddess. :)

I'm thinking of a photograph of a completely veiled Muslim woman, with just one eye showing. She is holding a gun aimed at the viewer. Now there is a real transgression in that photograph, but not really much sex.

So I don't think that censure is needed to get art but censure can't stop art from existing and it will exist in a different form because of the censuring.

The economics of art are interesting, but in some ways they give similar limits or constraints to art and make it appear in unusual ways. Think about the Nightwatch and how Rembrandt chose to make the people all different sizes even though they all paid the same amount to get included. I wouldn't have wanted to be in the meeting afterwards...

Having sexuality in art is not necessary, but it's one of the few things that tends to be censured to even the most powerful ones in society, so in that sense it always interests. For the rest of the people many other things are censured and banned and in that sense serve the role of "the nasty" to the privileged few. Just my opinion, of course, and I have no training in these fields, being a goddess. :)

I'm thinking of a photograph of a completely veiled Muslim woman, with just one eye showing. She is holding a gun aimed at the viewer. Now there is a real transgression in that photograph, but not really much sex.

So if it is not merely sexual or even religious transgression in the modern period that makes art suceptible to "outrage," what is it about the formal transgressions that provokes what we might call the "censorship impulse"?

Well, the discussion has changed for me with this question, so I'll have to get back to you! But when you asked initially about the relationship between art and cendorship, my first naive reductionist response was that death is the ultimate censorship. So all creation rises up from those, uh, ashes, if you will...

Post a Comment

Well, the discussion has changed for me with this question, so I'll have to get back to you! But when you asked initially about the relationship between art and cendorship, my first naive reductionist response was that death is the ultimate censorship. So all creation rises up from those, uh, ashes, if you will...

<< Home