Monday, June 12, 2006

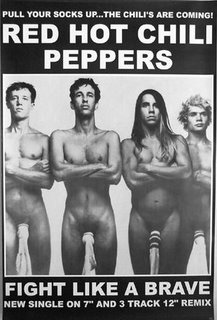

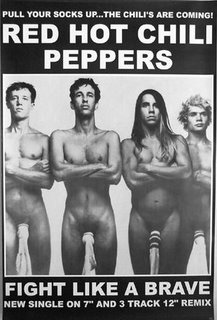

Socks

This is trivial, in some ways, but it is in its own way a nice little illustration of some of the principles we've been discussing.

Above see a poster of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who for years were known for ending their shows by performing clad only in sweatsocks affixed over their penises. Very good. Now, this afternoon I was switching channels and happened across some VH1 program documenting this phenomenon. It showed footage of the, uh, sockage, and ended with a brief interview with the singer, Anthony Kiedis. Mr. Kiedis explained how the idea got started, and how much fun it was to be on stage naked except for an "exagerrated phallus." He then said (and this is the punchline) that eventually the band had to stop doing it, because "people were starting to think it was just a gimmick." (It was making people think the band's performances were "not about the music." Yes, he really said that.)

Now, this is an astonishing statement. Of course the socks-wearing was a gimmick. And as these things go, it was a pretty good gimmick. It helped them become better known, said something about the image the band wanted to project, and was, frankly, not very easy to forget. And then, understandably, it got a bit old, and they stopped doing it. So what's the big deal? Why the perceived need to distance yourself from something that, while bizarre, clearly helped your career?

The answer is to do with the logic of the field of "alternative" music from whence the RHCP emerged. The band always quite clearly wanted to become popular, but stating this as a goal would violate the first rule of the field of restricted production: "success" can only be legitimately attained if it is defined in artistic terms, not in the ordinary terms of money and popularity. The disdain of indie-music scenesters for such rewards is of course legendary. And while this sort of sneering of course is easily mocked as ridiculous, one really cannot deny the potentially devastating force of the accusation or potential accusation. So a "tipping point" was reached for the socks on the cocks: they came off and the undies came on when the band began to fear that the stunt would be perceived not as a rebellious act, a natural outgrowth (beg pardon) of their happy-nature-boy screw-conventional-standards ethos, but as a calculated attempt to get attention and notoriety and thus fame and money, etc. That would lose them credibility -- and, paradoxically, sales. Be seen as a "sellout" and you risk not being able to sell anything. So, in a paradoxical and confounding way, to make a finacial profit, everything for the artist who wishes to be seen as "independent" depends on a firm disavowal of the exclusive desire to make a financial profit.

Now, there is of course a further wrinkle to all this. Mr. Kiedis could have said (and hell, probably has at some point) that he is sick of the scenesters who are always accusing his band of being "sellouts." This is a fairly typical move. (Ripley mentions in comments how this happened with Green Day as they began to sell more and more records.) The key point to remember here is that the underlying principle for attaining "legitimacy" in such circles depends on a logic of reversal. The first reversal: that of the field of general production (money and fame). OK, so your band builds up a following, gets a deal, becomes popular, and then -- bam, predictably, comes the accusation of "selling out." So what's the answer? Well, another reversal, this time involving a repudiation of the "scene." Such reversals usually involve the accusation that it is the band's erstwhile followers who cannot understand how the music is evolving according what is most often described as a "natural" progression of the artistic vision: the hipsters are merely pursuing the grubby rewards of small-time prestige while the band has moved on. (Yes, bands will often concede that getting rich is pretty cool, but their ultimate justification is pretty much always the music, man.)

Anyway, rock music, especially in its indie or alternative or whatever areas, one where there is a "scene," is an especially instructive place to look for illustrations of the dynamics I'm talking about. This is because the distance between "freedom" and Art on the one hand and "selling out" and Crap on the other is so very narrow. The pressures exerted by the field on musicians and performers and scenesters, the constant demand for "legitimacy," are incredibly powerful. So much so that the same story seems to be told over and over and over again, often in almost exactly the same language, only with different names. (Ever notice how many times you've heard a band say they resent being "labelled"? It's always very revealing when someone uses what amounts to a cliche to explain that they do not wish to be reduced to a cliche. That is the pressure of the field, man.)

This is trivial, in some ways, but it is in its own way a nice little illustration of some of the principles we've been discussing.

Above see a poster of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who for years were known for ending their shows by performing clad only in sweatsocks affixed over their penises. Very good. Now, this afternoon I was switching channels and happened across some VH1 program documenting this phenomenon. It showed footage of the, uh, sockage, and ended with a brief interview with the singer, Anthony Kiedis. Mr. Kiedis explained how the idea got started, and how much fun it was to be on stage naked except for an "exagerrated phallus." He then said (and this is the punchline) that eventually the band had to stop doing it, because "people were starting to think it was just a gimmick." (It was making people think the band's performances were "not about the music." Yes, he really said that.)

Now, this is an astonishing statement. Of course the socks-wearing was a gimmick. And as these things go, it was a pretty good gimmick. It helped them become better known, said something about the image the band wanted to project, and was, frankly, not very easy to forget. And then, understandably, it got a bit old, and they stopped doing it. So what's the big deal? Why the perceived need to distance yourself from something that, while bizarre, clearly helped your career?

The answer is to do with the logic of the field of "alternative" music from whence the RHCP emerged. The band always quite clearly wanted to become popular, but stating this as a goal would violate the first rule of the field of restricted production: "success" can only be legitimately attained if it is defined in artistic terms, not in the ordinary terms of money and popularity. The disdain of indie-music scenesters for such rewards is of course legendary. And while this sort of sneering of course is easily mocked as ridiculous, one really cannot deny the potentially devastating force of the accusation or potential accusation. So a "tipping point" was reached for the socks on the cocks: they came off and the undies came on when the band began to fear that the stunt would be perceived not as a rebellious act, a natural outgrowth (beg pardon) of their happy-nature-boy screw-conventional-standards ethos, but as a calculated attempt to get attention and notoriety and thus fame and money, etc. That would lose them credibility -- and, paradoxically, sales. Be seen as a "sellout" and you risk not being able to sell anything. So, in a paradoxical and confounding way, to make a finacial profit, everything for the artist who wishes to be seen as "independent" depends on a firm disavowal of the exclusive desire to make a financial profit.

Now, there is of course a further wrinkle to all this. Mr. Kiedis could have said (and hell, probably has at some point) that he is sick of the scenesters who are always accusing his band of being "sellouts." This is a fairly typical move. (Ripley mentions in comments how this happened with Green Day as they began to sell more and more records.) The key point to remember here is that the underlying principle for attaining "legitimacy" in such circles depends on a logic of reversal. The first reversal: that of the field of general production (money and fame). OK, so your band builds up a following, gets a deal, becomes popular, and then -- bam, predictably, comes the accusation of "selling out." So what's the answer? Well, another reversal, this time involving a repudiation of the "scene." Such reversals usually involve the accusation that it is the band's erstwhile followers who cannot understand how the music is evolving according what is most often described as a "natural" progression of the artistic vision: the hipsters are merely pursuing the grubby rewards of small-time prestige while the band has moved on. (Yes, bands will often concede that getting rich is pretty cool, but their ultimate justification is pretty much always the music, man.)

Anyway, rock music, especially in its indie or alternative or whatever areas, one where there is a "scene," is an especially instructive place to look for illustrations of the dynamics I'm talking about. This is because the distance between "freedom" and Art on the one hand and "selling out" and Crap on the other is so very narrow. The pressures exerted by the field on musicians and performers and scenesters, the constant demand for "legitimacy," are incredibly powerful. So much so that the same story seems to be told over and over and over again, often in almost exactly the same language, only with different names. (Ever notice how many times you've heard a band say they resent being "labelled"? It's always very revealing when someone uses what amounts to a cliche to explain that they do not wish to be reduced to a cliche. That is the pressure of the field, man.)

Comments:

<< Home

Well, another reversal, this time involving a repudiation of the "scene." Such reversals usually involve the accusation that it is the band's erstwhile followers who cannot understand how the music is evolving according what is most often described as a "natural" progression of the artistic vision: the hipsters are merely pursuing the grubby rewards of small-time prestige while the band has moved on.

This, um, sounds a bit like the Democratic party and their oh-so-pragmatic-and-realistic DLC svengalis...

This, um, sounds a bit like the Democratic party and their oh-so-pragmatic-and-realistic DLC svengalis...

Anyway, rock music, especially in its indie or alternative or whatever areas, one where there is a "scene," is an especially instructive place to look for illustrations of the dynamics I'm talking about. This is because the distance between "freedom" and Art on the one hand and "selling out" and Crap on the other is so very narrow. The pressures exerted by the field on musicians and performers and scenesters, the constant demand for "legitimacy," are incredibly powerful.

This is exactly right and very well said. What's funny is that these artists usually reach some crisis point: "How can I go on being legitimate?" But as you suggest (I think), the question is basically self-flattery. One was never legitimate in the standard romantic sense. One was always competing within a marketplace - for attention if not for money - and with one eye checking to see what other people were doing in order to position oneself accordingly.

Of course, people make great art and music all the goddamn time, and always have. Which suggests that these issues are simply not very important, qualitatively. And yet, we're culturally hung up on them. We often don't like anyone to talk about the calculation and compromise involved in producing art that we like.

The punchline is that a lot of the hipsters who put so much energy and so many years into demonstrating their authenticity and sense of style often end up listening to, say, Gino Vanelli or Jan Hammer, in order to prove that they're not concerned with seeming cool. The apotheosis of hipsterdom is to sit alone in an empty room.

This is exactly right and very well said. What's funny is that these artists usually reach some crisis point: "How can I go on being legitimate?" But as you suggest (I think), the question is basically self-flattery. One was never legitimate in the standard romantic sense. One was always competing within a marketplace - for attention if not for money - and with one eye checking to see what other people were doing in order to position oneself accordingly.

Of course, people make great art and music all the goddamn time, and always have. Which suggests that these issues are simply not very important, qualitatively. And yet, we're culturally hung up on them. We often don't like anyone to talk about the calculation and compromise involved in producing art that we like.

The punchline is that a lot of the hipsters who put so much energy and so many years into demonstrating their authenticity and sense of style often end up listening to, say, Gino Vanelli or Jan Hammer, in order to prove that they're not concerned with seeming cool. The apotheosis of hipsterdom is to sit alone in an empty room.

What's funny is that these artists usually reach some crisis point: "How can I go on being legitimate?" But as you suggest (I think), the question is basically self-flattery. One was never legitimate in the standard romantic sense. One was always competing within a marketplace - for attention if not for money - and with one eye checking to see what other people were doing in order to position oneself accordingly.

FWIW, Phila, this is basically Thers's analysis of the suicide of Kurt Cobain.

FWIW, Phila, this is basically Thers's analysis of the suicide of Kurt Cobain.

How to travel from smut to sellout in three easy posts!!!

I think you're also forgetting that there is an age factor at work here. What was kuhl and hip to the artist at 22, in terms of music and lifestyle, may've become unpleasant and juvenile by 35. But music has a powerful emotional componenet so the listeners want the musician to remain a part of the glory days.....

(Hee. Today's word verification is vodcka and its only 9:15 am)

I think you're also forgetting that there is an age factor at work here. What was kuhl and hip to the artist at 22, in terms of music and lifestyle, may've become unpleasant and juvenile by 35. But music has a powerful emotional componenet so the listeners want the musician to remain a part of the glory days.....

(Hee. Today's word verification is vodcka and its only 9:15 am)

Phila -- I think the issues are important, qualitatively. The structure of the field is usually present in the artistic work itself, as a homology. This may sound like a great leap of logic, but it's really a very simple point. To do something new or different artistically you need to know what's been done before, or at least have absorbed what's gone before, so you know what rules to break that will move you forward, and what rules not to break that will disqualify you from legitimacy. More on this later...

But music has a powerful emotional componenet so the listeners want the musician to remain a part of the glory days.....

An artist distancing his or herself from their older works, particularly in our short-attention-span culture, is a sure-fire way to bring that charge of "sell out". Or even just a loss of interest from the fanbase.

I can remember seeing The Smashing Pumpkins not long before their demise and listening to Billy Corgan go on about how embarrassing the band's early work was. I found that incredibly insulting and it pretty much lost me as a fan (I don't own their last several albums). Certainly a discussion could be had on the artistic merits of Corgan's music, but regardless of its value in that sense it was very important to me in my formative teenage years. In that sense, his work, or at least the perception of its importance, belonged to me and I was unhappy to have it taken away, even by the artist.

Perhaps that's what Thers means by one of the rules not to be broken?

An artist distancing his or herself from their older works, particularly in our short-attention-span culture, is a sure-fire way to bring that charge of "sell out". Or even just a loss of interest from the fanbase.

I can remember seeing The Smashing Pumpkins not long before their demise and listening to Billy Corgan go on about how embarrassing the band's early work was. I found that incredibly insulting and it pretty much lost me as a fan (I don't own their last several albums). Certainly a discussion could be had on the artistic merits of Corgan's music, but regardless of its value in that sense it was very important to me in my formative teenage years. In that sense, his work, or at least the perception of its importance, belonged to me and I was unhappy to have it taken away, even by the artist.

Perhaps that's what Thers means by one of the rules not to be broken?

Phila -- I think the issues are important, qualitatively. The structure of the field is usually present in the artistic work itself, as a homology. This may sound like a great leap of logic, but it's really a very simple point.

Yeah, but I meant "not very important qualitatively" in the sense of not necessarily affecting one's ability to do good and lasting work, not in the sense of "having no bearing on how the work turns out."

A lot of people assume that compromise and so forth automatically detract from or destroy the artist's "vision" or "authenticity"; that sets up a false dichotomy, I think, given that compromise is inevitable and authenticity is a dubious concept at best.

It's interesting to think about how the economics and mechanics of Victorian serialization affected the way Dickens went about writing certain novels, but it's also immaterial to their status as works of art, IMO. The search for purity of expression or intent in art is a silly one, is all I'm saying. (But then again, if my favorite artist is "authentic," it reflects well on me. Doesn't it?)

FWIW, Phila, this is basically Thers's analysis of the suicide of Kurt Cobain.

Sounds pretty accurate to me, as far as the "artistic" side of things goes. Of course, there may've been other issues, too.

Yeah, but I meant "not very important qualitatively" in the sense of not necessarily affecting one's ability to do good and lasting work, not in the sense of "having no bearing on how the work turns out."

A lot of people assume that compromise and so forth automatically detract from or destroy the artist's "vision" or "authenticity"; that sets up a false dichotomy, I think, given that compromise is inevitable and authenticity is a dubious concept at best.

It's interesting to think about how the economics and mechanics of Victorian serialization affected the way Dickens went about writing certain novels, but it's also immaterial to their status as works of art, IMO. The search for purity of expression or intent in art is a silly one, is all I'm saying. (But then again, if my favorite artist is "authentic," it reflects well on me. Doesn't it?)

FWIW, Phila, this is basically Thers's analysis of the suicide of Kurt Cobain.

Sounds pretty accurate to me, as far as the "artistic" side of things goes. Of course, there may've been other issues, too.

Back when young Zap was in a punk rawk band, you had different levels of selling out. When a local band signed to Fat Wreck Chords some years back, that was seen as a sell out because Fat is/was owned by a guy from NOFX, IIRC. And NOFX is/was always on the Vans Warped Tour. The "Crusty Punks" hate that shit.

Of course, we were all 21 years old then...and dumb.

I don't like Green Day anymore because I learned more than three chords on the guitar, not because they don't/can't charge $3 for tickets anymore.

And if I remember correctly, I thought that the RHCP stopped that sock bit way before they hooked up with Rick Rubin and got rich...

Of course, we were all 21 years old then...and dumb.

I don't like Green Day anymore because I learned more than three chords on the guitar, not because they don't/can't charge $3 for tickets anymore.

And if I remember correctly, I thought that the RHCP stopped that sock bit way before they hooked up with Rick Rubin and got rich...

I'm feel like I've been more than usually incoherent lately, so I thought I'd bring up an example of what I'm talking about. A month or two ago, folks at Eschaton were talking about Orson Welles. I mentioned that IMO, "The Magnificent Ambersons" was his best movie, and maybe his only great one.

According to someone or other, that was a ludicrous thing to say, because the studio had "butchered" TMA and it'd thus been sullied beyond redemption by philistinism (the tacked-on happy ending being the biggest complaint).

Of course, there's no obvious reason why a butchered film couldn't be an director's best work. Plus, I've read Welles' script, and I'm not convinced that his ending was the right one, either. And I'm also not convinced that a tacked-on happy ending really sullies the film, any more than a deus ex machina sullies a play by Euripedes. And last, there's clear evidence that Welles himself was responsible for the worst of the butchery, and that his own account of the matter would be highly suspect even if he weren't an inveterate liar.

So in the end, the "authenticity" of the film really isn't an issue to me. In addition to being a great movie, it has the virtue of being an unusually stark illustration of the messiness - personal and professional - that's usually involved in creating works of art. People who'd write it off simply for not being true to Welles' "intent" are living in a romanticist dreamworld, I think.

You can't blame them, though, 'cause this whole narrative of the authentic artist who fights a heroic battle against philistinism is one of the most compelling myths we have. One of the most lucrative, too, if you play your cards right.

According to someone or other, that was a ludicrous thing to say, because the studio had "butchered" TMA and it'd thus been sullied beyond redemption by philistinism (the tacked-on happy ending being the biggest complaint).

Of course, there's no obvious reason why a butchered film couldn't be an director's best work. Plus, I've read Welles' script, and I'm not convinced that his ending was the right one, either. And I'm also not convinced that a tacked-on happy ending really sullies the film, any more than a deus ex machina sullies a play by Euripedes. And last, there's clear evidence that Welles himself was responsible for the worst of the butchery, and that his own account of the matter would be highly suspect even if he weren't an inveterate liar.

So in the end, the "authenticity" of the film really isn't an issue to me. In addition to being a great movie, it has the virtue of being an unusually stark illustration of the messiness - personal and professional - that's usually involved in creating works of art. People who'd write it off simply for not being true to Welles' "intent" are living in a romanticist dreamworld, I think.

You can't blame them, though, 'cause this whole narrative of the authentic artist who fights a heroic battle against philistinism is one of the most compelling myths we have. One of the most lucrative, too, if you play your cards right.

Zap -- can't remember when the RHCP stopped the socks bit. Sometime in the 90s. But the point is the why... the line "people were thinking it was just a gimmick" is priceless. Who cares if it was a gimmick? What's wrong with gimmicks? But overall you're right -- as soon as you take a step back from all these categories of what is and is not authentic, the more bizarre they seem. The question is, how come so many people think this way? Where did these ideas come from?

This is because the distance between "freedom" and Art on the one hand and "selling out" and Crap on the other is so very narrow.

Well, you know, I still haven't gotten over Dylan going electric....

Actually, I was thinking about this just the other day (I think the lower thread inspired me). "Folk music," the "real," "anonoymous" stuff, arose as a form of entertainment, but also as a matter of expression of hard times, lost love, gettin' through the day, human foibles, etc., etc. Listen to some of it (it is my favorite of favorite forms of song), the range of concerns is extraordinary.

It wasn't written for a market.

Rock 'n' roll pretty much started with Elvis, who wed blues beats (the term itself comes from blues patois, it means "makin' the beast with two backs") and "black music" to white songs (basically; hey, it's a comment, my space is limited!). And he did it to sell records (not for his momma!). It worked, and here we are today.

Rock 'n' roll, IOW, has ALWAYS been about marketing, and the bigger the market, the better. Folk music was always confined to a lower strata (it came out of the closet thanks to Romanticism, but that's another analysis). So rock 'n' roll is always caught in that dynamic identified in the quote above.

But the question remains: is it Art?

Post a Comment

Well, you know, I still haven't gotten over Dylan going electric....

Actually, I was thinking about this just the other day (I think the lower thread inspired me). "Folk music," the "real," "anonoymous" stuff, arose as a form of entertainment, but also as a matter of expression of hard times, lost love, gettin' through the day, human foibles, etc., etc. Listen to some of it (it is my favorite of favorite forms of song), the range of concerns is extraordinary.

It wasn't written for a market.

Rock 'n' roll pretty much started with Elvis, who wed blues beats (the term itself comes from blues patois, it means "makin' the beast with two backs") and "black music" to white songs (basically; hey, it's a comment, my space is limited!). And he did it to sell records (not for his momma!). It worked, and here we are today.

Rock 'n' roll, IOW, has ALWAYS been about marketing, and the bigger the market, the better. Folk music was always confined to a lower strata (it came out of the closet thanks to Romanticism, but that's another analysis). So rock 'n' roll is always caught in that dynamic identified in the quote above.

But the question remains: is it Art?

<< Home